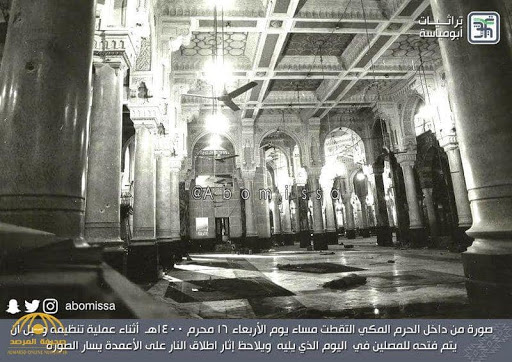

In 1979 leading up to the Hajj Pilgrimage, Masjid Al Haram was renovated. In particular, the Mihrab which was located inside Masjid Al Haram was removed, along with the entrance of Bani Sheba. The entire surface of the Mataf was paved with white marble. Furthermore, the Azan room (Al Mukabariya) which was inside the Mataf was also demolished and work began on its construction from inside the Ottoman porticoes.

The King of Saudi Arabia at the time was Khalid bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud, and his brother Fahad bin Abdul Aziz was Crown Prince.

Three main Imams would lead the Salat that year; Sheikh Abdullah Khayyat, Sheikh Abdullah Khulaifi and Sheikh Muhammad Subbail.

On the morning of the first day of the new Islamic year, many of the Hajj pilgrims who had stayed in Makkah began to congregate inside Masjid Al Haram for Fajr Salaat.

The first Azan of Fajr (Tahajjud Azan) was called by Sheikh Abdul Malik Mulla, cousin of the current Muezzin of Makkah Sheikh Ali Ahmed Mulla. This was done in the new Mukabariya which was in the latter stages of completion. The second Azan for Fajr (main Azan) was called by Sheikh Abdul Hafeez Khoja, father of current Muezzin of Haram Sheikh Tawfeeq Khoja.

The Salat was led by the Imam Sheikh Muhammad Subbail, which began and ended as usual.

The next day a group led by Juhayman al-Otaibi made their way into Masjid Al Haram’s inner sanctum, well-armed. The time was just before Fajr Salat and the Imam, Sheikh Muhammad Subbail was preparing to lead the worshippers in prayer.

Just after 5 am, before any of the thousands of pilgrims, there could comprehend what had happened, the rebel leader took control of the microphones at the front of the mosque, announcing that the Mahdi had arrived in the form of his brother-in-law.

The event started what would become a war inside Masjid Al Haram, Makkah.

Sheikh Muhammad Subbail was preparing to lead the worshippers in Fajr Salat on the morning of the seizure. His reaction after the events of the day was narrated by the late Imam of Makkah.

Sheikh Muhammad Subbail was shoved away at the front of the row of worshippers near to the Kaaba by the Juhayman group. After the first shots were fired, the Imam managed to take off his cloak and vanish into the crowd. Running for his life, the 55-year-old Imam at the time headed to his office above Fatah gate near to Safa Palace which overlooked the Grand Mosque.

Sheikh Subbail immediately rang his superior, Sheikh Nasser ibn Rashid. He glanced out of the window and saw more members of the Juhayman group entering Masjid Al Haram, some even with vehicles.

After making the phone call, the Imam of the holiest place in Islam returned downstairs and began his approach to escape Masjid Al Haram alive.

Once returning back to the ground of Masjid Al Haram, Sheikh Muhammad Subbail began to plan his escape and accessed the office of the Grand Mosque police force. However, the Juhayman Group did not allow everyone to leave, many were targeted and made to join the plans of the group.

Being the Imam of Masjid Al Haram, the status and appearance of Sheikh Muhammad Subbail was known to many of the pilgrims and Juhayman members.

Realizing that he would need to disguise his appearance, Sheikh Subbail pulled down his Shemagh head scarf and wrapped it around his shoulders in the manner of foreigners. He then joined a group of distressed Indonesian pilgrims trying to blend in.

Juhayman had no use of Indonesian pilgrims who did not speak nor understand Arabic. They were released without harassment, and the Imam of Kaaba, too, managed to slip out unnoticed.

Masjid Al Haram was closed for Muslims for the first time in centuries. No Salat, Tawaf, Sa’ee, or other acts of worship were performed inside the holiest place in Islam for days.

The Saudi authorities had to either immediately crush the aggressors of the Juhayman group or call on them to lay down their arms. The government sent the attackers a warning through microphones stressing that what the deviant group inside the Holy Mosque were doing was in complete contradiction to the teachings of Islam.

The warning, in the name of the government of the late King Khaled, also included the following Qur’anic verse to remind the attackers of their heinous acts: “Whoever intends a deviant deed at the Holy Mosque, in religion, or wrongdoing, We will make him taste a painful punishment,” and “Do they not then see that We have made a sanctuary secure, and that men are being snatched away from all around them? Then, do they believe in that which is vain, and reject the Grace of Allah?”

However, all calls on the attackers to surrender were fruitless. From the high minarets of the sacred mosque, snipers started gunning down innocent people outside the Grand Mosque.

The Juhayman group released most of the hostages and locked the remainder in the sanctuary. They took defensive positions in the upper levels of the mosque, and sniper positions in the minarets, from which they commanded the grounds.

No one outside Masjid Al Haram knew how many hostages remained, how many militants were in the mosque and what sort of preparations they had made.

At the time of the event, Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdul Aziz was in Tunisia for a meeting of the Arab Summit and then commander of National Guard Prince Abdullah was in Morocco for an official visit. Therefore, King Khalid assigned the responsibility to Prince Sultan, then Minister of Defense and Prince Nayef, then Minister of Interior, to deal with the incident.

Saudi Arabia traditionally broadcast the Friday Sermon (Khutbah) on Saudi TV and Radio. On Friday, 23 November 1979 (3 Muharram 1400 Hijri), Muslims across the world waited for noon in Makkah.

However, on this particular Friday, there was no broadcast from Makkah. The Jumu’ah Salat did not occur in Masjid Al Haram for the first time in centuries. As an alternative, Saudi radio transmitted a sermon from the Imam of Prophet’s Mosque in Madinah, Sheikh Abdul Aziz bin Saleh.

Men occupying the Grand Mosque, Sheikh Abdul Aziz Bin Saleh shrieked, were “criminals exploiting the sanctity of the shrine…. to slaughter innocent people, performing their devotions.”

To millions of Muslims worldwide, the absence of a Friday Sermon from Makkah came as a shock.

As the siege wore on, the Interior Minister Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz concluded that his security forces were no match for the rebels cached in the Masjid Al Haram manifold nooks and crannies.

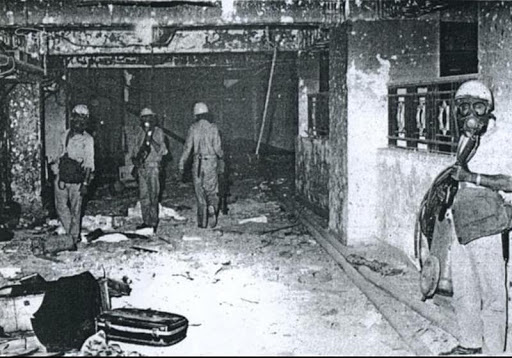

Consequently, he called on France’s elite counterterrorism and hostage rescue force, the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group (GIGN) to help end the crisis. The kingdom maintained a close intelligence relationship with France, and the GIGN had reportedly impressed bin Abdulaziz at a recent demonstration. The interior minister likely realized, moreover, that the kingdom needed discretion above all else, something that the United States — by then mired in the early stages of the Iranian hostage crisis — probably couldn’t give them. Four members of the French force were soon traveling to Saudi Arabia in secret to devise a viable counterassault before the world caught wind that the House of Saud had lost control of the mosque, one of the bases of its legitimacy. (Their journey allegedly included a conversion to Islam so that the Frenchmen could enter the holy city of Makkah.)

As the former head of the GIGN Paul Barril tells it, the ill-equipped Saudi military needed to disrupt the rebels from a distance to avoid another bloodbath. The French operatives settled on using a gas that caused vomiting and temporary blindness to incapacitate the militants, allowing Saudi security forces and a contingent of Pakistani commandos to penetrate the Grand Mosque. Many of the rebels retreated into the recesses underneath the structure, and from there, a brutal battle erupted. Saudi forces indiscriminately threw grenades, killing untold numbers of pilgrims, military personnel and rebels. Official estimates put the death toll at around 255.

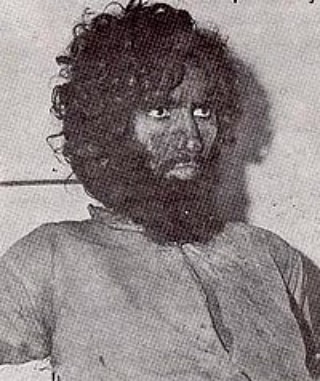

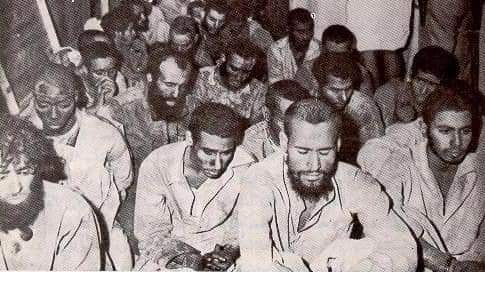

After 15 days, Saudi security forces managed to neutralize the militants and kill the proclaimed Mahdi. The government even kept news of the siege mostly under wraps, though the incident would become fodder for the growing jihadist movement in the decades ahead. Security forces captured al-Otaibi, along with several of his confederates, and paraded them in front of Saudi media before most of them were beheaded.